For several decades now, I've been a student, observer and participator in strategy (corporate, branding and marketing) and organization - getting these right is, of course, critical to success. But I've seen many cases where carefully prepared plans and their support structures have not resulted in the desired results.

Reading To Rule the Waves, a gripping history by Arthur Herman, I was struck by the role communications played in two Royal Navy engagements, 25 years apart, each of immense strategic consequences: Yorktown in 1781 and Trafalgar in 1805.

Communications dictated the outcome of each, one a failure that lost a continent and one a victory that established naval pre-eminence for more than a century. The lesson: everyone in the organization must understand what needs to be done for a plan to be successfully executed.

Yorktown

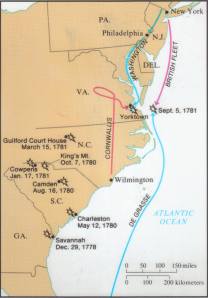

In late 1781, "a British army under General Cornwallis had been driven back across Virginia to Yorktown at the mouth of the James River. A French squadron of 26 ships of the line under Admiral de Grasse had cut off Cornwallis. The North American [British] squadron under its new commander Thomas Graves had come down into the Chesapeake Bay to drive de Grasse away; at Virginia's Cape Henry the fleets joined battle on September 5."

It was a fight the British should have won. Grave's subordinate, Samuel Hood, wrote to [Lord] Sandwich, 'Yesterday the British fleet had a rich and most delightful harvest of glory presented to it, but omitted to gather it." Instead, a confusion of signals (Graves had run up the signal for close action at the same time as the flag for keeping the line of battle), and de Grasses's skill in avoiding a more decisive engagement cost Graves the battle and sent him back to New York. By the time he returned, Cornwallis had surrendered. The American War of Independence had been won and lost."

Within a decade, however, the British Navy would introduce a new communications system so revolutionary that it would change the way naval battles were fought, and result in a victory so decisive that Britain would would dominate the world's oceans for over a century.

Historically, admirals could communicate with their captains by the placement and color of flags raised and lowered from the flagship's (hence the name...) masts. Unfortunately, the captains couldn't communicate back and, worse, the admiral couldn't change plans in the heat of the battle. That changed in 1790, when

Richard Howe introduced a new numerical system for signalling his captains, with 10 flags of standard pattern and color (the basis of the International Code of signals still used by ships today). They could now be used in combination to form more than 260 separate messages, from the admiral to his ships but also now from his ships to the admiral. There was even a signal for telling the admiral his signal had been seen and understood, resolving a confusion that had plagued every naval commander since the Spanish Armada - and which had lost Britain the battle of the Chesapeake, and the American Revolution.

Trafalgar

The Treaty of Amiens, signed in 1802, had two results: it ended the the hostilities between France and Britain during the French revolutionary war and, more importantly, made Napolean the military master of the continent of Europe. Only Britain stood in the way of his perceived destiny.

So when, inevitably, war with Britain resumed in May 1803 (the pretext was Britain's refusal to evacuate Malta as promised), Napolean focused his energies on the achievement that had eluded everyone since William the Conqueror: the invasion and defeat of Britain...Like Philip II two centuries earlier, he summoned all the resources of his continental empire. Napolean assembled at Boulogne the battle-hardend veterans of a dozen campaigns into a force of 160,000 men, which he dubbed the Grand Army. He poured over maps and chose the location for his beachhead lading: the northeast coast between Deal and Ramsgate, where his invasion force could anchor in the Downs in the shelter of the Goodwin Sands. He had his engineers design special boats that could get across the Channel in a dead calm.

The only obstacle was the Royal Navy, and in particular the Mediterranean fleet under the command of Horatio Nelson, and his flagship, Victory, which would become the most famous man-of-war in British history. His goal was "'to keep the French fleet in check, and if they out to see, annihilate him.' To do this, Nelson would use a new kind of blockade, not close but loose - so loose, in fact, that it might tempt the French to break out and then fall into his trap. He had a tool to help him: the new navy signals." By 1799 the Admiralty had adopted and expanded the system to more than 340 messages, giving an admiral unprecedented tactical control.

Over the next two years, British and French naval forces played a game of cat and mouse in the Mediterranean, Atlantic and Caribbean, each trying to gain an advantage that would seriously cripple the other. In September 1805, Admiral Pierre de Villeneuve, commander of Napolean's fleet, was preparing to go to sea from Cadiz, Spain to try to secure the English Channel when an order arrived from Napolean: his enemies were gathering in central Europe and the fleet now needed to return to the Mediterranean to land troops and supplies in Naples. As the French fleet set sail on October 19,

The [British] frigate Sirius was the first to spot them. It immediately sent the news on to Blackwood's Eurylalus [using 26 flags: 'To Eurayalus: Enemy have their topsails hoisted.'...which] relayed the message on to the next frigate, the Phoebe, and so on until it reached the Mars 48 miles away. Lt. William Cumby of the Bellerophon then caught the Mars signal; his captain was planning to dine with Nelson on the Victory that very morning. Now Captain Cooke had more exciting news to pass on to his commander in chief: the French were coming.

Two days later, the enemy fleets engaged and the British won a decisive victory that, in their minds, buried any chance of Napolean's invasion of England, even though it was later learned that he had called off the invasion. However, the victory did ensure that Britain would remain unchallenged as it established control of the oceans for the better part of the next century. While tactics, bravery and luck - good and bad: Nelson lost his life - played an important role, as in any armed conflict, the ability of the British fleet to act swiftly on intelligence that would not have been able to be communicated a decade before was crucial.

![horatio_nelson1[2]](http://davidharkleroad.files.wordpress.com/2010/06/horatio_nelson12.jpg?w=123)

No comments:

Post a Comment